Research

Research

Research

A brief history of 75 (NZ) Squadron RAF

This history is shared from the 75(NZ) RAF Squadron website, an enormously valuable resource.

75 Squadron aircrew with a Wellington Mk I in the background at RAF Feltwell

The history of 75(NZ) Squadron RAF started in 1938 when the New Zealand government ordered 30 Vickers Wellington bombers. In early 1939 air and ground crews arrived in England to train on the new aircraft. The unit was officially known as the New Zealand Flight, based at Harwell.

When war was declared on the 3rd of September 1939, the New Zealand government waived its claim to the bombers and put them at the disposal of the Royal Air Force. The New Zealand government requested that a squadron be formed from the New Zealand Flight.

Training continued, also the build-up of aircraft and personnel. Many New Zealanders serving in the Royal Air Force volunteered to serve with the unit.

On the 1st of April 1940 the number plate of 75 Squadron, Royal Air Force was transferred to the New Zealand Wellington Flight, creating 75 (New Zealand) Squadron, operating from Feltwell in Norfolk. The squadron operated within 3 Group, Bomber Command until July 1945 and was then transferred to 5 Group.

Early operations carried out were leaflet dropping over Germany, searching the North Sea for German naval ships and attacking targets in Norway during the German invasion of that country. On May the 10th German forces invaded through the Low Countries of Holland and Belgium to attack France. 75 were thrown into the thick of the action attacking communication networks in an attempt to halt the German advance. The squadron’s first loss occurred on the night of 20/21 May when Flight Lieutenant John Collins, RNZAF, and his crew were shot down whilst attacking a bridge at Dinant, Belgium. Collins and the second pilot, Pilot Officer Francis De Labouchere-Sparling was both killed. The other three members of the crew being taken prisoner.

With the fall of France Bomber Command had the only means of taking the fight to the enemy. Coastal targets in France were attacked to destroy barges being prepared for the invasion of England. Industrial targets in Germany were attacked throughout the rest of 1940. Seven aircraft and crews failed to return during 1940 while others returned with dead or injured.

1941 saw a concerted effort in attacking industrial and navel targets within Germany. On the night of 7/8 July the target was Munster. Squadron Leader Ben Widdowson, a Canadian serving in the RAF, and his crew were attacked by a night –fighter returning from the target whilst over Holland. Damage was caused to the starboard engine and the petrol feed lines cut resulting in a fire. Efforts were made to extinguish the fire from within the aircraft without success. The second pilot, Sergeant Jimmy Ward RNZAF, secured only by a rope attached to Sergeant Joe Lawton RNZAF, climbed out of the aircraft and onto the wing stifling the flames with an engine cover. With superhuman effort Jimmy Ward crawled back into the fuselage. An emergency landing was made at Newmarket Heath on return. For his actions this night Jimmy Ward was awarded the Victoria Cross. Sadly, he was to lose his life on September 15 over Hamburg. 22 aircraft failed to return from operations during the year with again many returning with dead or wounded (for more on Jimmy Ward go to james-allen-ward-vc/)

Of those taken prisoner, Sergeant Jeffrey Reid RAF and Sergeant Lawrence Hope RNZAF were never to see home again. Jeff Reid was shot dead by prison camp guards in Poland on December 29, 1941, and Laurie Hope was killed on April 19, 1945, by RAF fighters that attacked the prisoner of war column in which he was marching, mistaking them for German troops.

The first operational losses for 1942 were on the night 12/13 March when the target was Kiel. Three aircraft failed to return with no survivors from the eighteen crewmembers. The 5/6 April saw the squadron going to Cologne. The operation was led by Wing Commander Reginald Sawrey-Cookson, DSO DFC RAF, and commanding officer of 75. Wing Commander Sawrey-Cookson was a young, determined commander who led from the front, never expecting of his crews what he himself was not prepared to undertake. He was not to return from this operation, being killed with the rest of the crew.

The leadership of Bomber Command had now been taken over by Air Chief Marshall Sir Arthur Harris under whose leadership the bombing campaign would take a new direction. Up until this time bombers had been sent out in small groups to various targets. Navigation and bomb aiming being as much luck as skill and judgment with the rudimentary devices available at that time. Arthur Harris’s task was to turn Bomber Command into a more efficient and effective force.

The objective of Arthur Harris was to show that bombing was and could be effective if deployed properly. There had been calls for Bomber Command to be disbanded and its resources distributed to other commands. To obtain the number of aircraft required training units were used alongside front line squadrons. The plan devised by Harris was to send one thousand bombers to attack one target. The idea being that the defences would be overwhelmed, and the target saturated with bombs. The target was Cologne on the night of 30 May when 75 dispatched twenty-three aircraft, losing one, that of Pilot Officer D.M. Johnson, RAF, the rear gunner being the sole survivor as a POW. The operation was a great success and secured the future of Bomber Command.

Operations continued to Germany and Italy with ever increasing losses due to improved night-fighter techniques and radar detection by German defenders.

In August 1942, the squadron moved to Mildenhall, Suffolk, and continued operations up to November when they converted to the Short Stirling four engined heavy bomber at Oakington. This also meant the addition of two extra crewmembers, a flight engineer and bomb aimer. The squadron being declared operational on the 20 November and moved to Newmarket, then in Cambridgeshire, carrying out an operation to Turin the same night. The first Stirling lost was on 2/3 December when Sergeant A. Scott, RNZAF, failed to return from Frankfurt, two being killed the rest POW. The rear gunner, Sergeant R.E. Preston, RAF, was to die on the 10 April 1945 during the forced march of POW away from the advancing Russian troops into Germany. The last losses for 1942 occurred on 2/3 December when four aircraft were lost attacking the Opal factory at Fallersleben. Wing Commander Victor Mitchell, DFC RAF, commanding officer, was killed. The crew of Flight Sergeant K. Dunmall, RAF, were all taken prisoner after being shot down over Holland. The bomb aimer, Pilot Officer Eric Williams, RAF, became famous for his escape from Stalag Luft 3 in 1943, being awarded the Military Cross on his return. Eric later wrote a book, ‘The Wooden Horse’, about the escape. It was later turned into a motion picture of the same name. Fifty aircraft and crews failed to return from operations, and a further twelve crashing in the U.K. or bringing back dead or wounded during the year.

With the New Year came improved navigation equipment allowing the bombers to find and attack their targets with greater accuracy.

Although the Stirling was a sound aircraft, its maximum operating height was 12000 feet, whereas the other heavy bombers, Lancaster and Halifax’s, operated at over twenty thousand feet. Not only were the Stirlings more vulnerable to anti-aircraft fire, but they were also in danger from the falling bombs of higher-flying aircraft.

Mixed operations were carried out to German and French targets as well as laying sea mines in enemy coastal waters. New crews were often given the task of mine laying for their first operation as these were considered safer.

During this period 75 took part in The Battle of the Ruhr, the industrial heartland of Germany. This was a very heavily defended target and losses reflected this.

In July, 75 moved yet again, to Mepal in Cambridgeshire, just outside of Ely, a brand-new aerodrome. From here they would fight the rest of war in Europe.

It must be said that without the dedication and hard work of the ground crews no operations could have taken place. Working in the open in most cases to repair or service aircraft sometimes in the most appalling weather conditions. Their efforts were as much a major factor in winning the air war as the aircrews that flew the operations.

In August, the Battle of Berlin commenced. Nine aircraft and crews were lost attacking this target between August and November.

Because of the high loss rate of Stirlings it was decided to take them off main force operations. They were relegated to mine laying, equipment drops to the French resistance and attacking rocket sites in occupied France.

Sixty-two aircraft failed to return from operations and a further fourteen crashed on return or brought back dead or wounded. One crashed during a training flight.

The first loss of 1944 occurred on 24/25 February when Pilot Officer H. Bruhns, RNZAF, failed to return from mine laying to Kiel Bay. The last Stirling to be lost was on 23/24 April when Pilot Officer M. Lammas, RNZAF, failed to return, again mining in Kiel Bay.

By now the squadron was starting to reequip with the Avro Lancaster, the first arriving on the 13 March.

75 (NZ) Squadron RAF

The first operation with Lancaster’s took place on the 9/10 April. Eleven aircraft attacking the railway yards at Villeneuve-St-Georges. All returned safely.

Stirlings were gradually phased out as Lancaster’s took over.

The first loss of a Lancaster occurred on the 27/28 April when Flying Officer R.W. Herron RNZAF failed to return from Friedrichshafen. There were no survivors.

75 were now back on main force operations attacking targets in Germany as well as supporting the Allied invasion of France.

The squadron was pleased with their new aircraft, being able to operate at a higher altitude. Losses compared to the number of operations and aircraft flown were very light until the night of 20/21 July when the target was Homberg. Twenty-six aircraft took off but only nineteen returned. Of the forty-nine crewmembers on the missing aircraft, forty-one were killed, seven made POW and one evaded capture.

Although better aircraft and equipment made the job of aircrew easier and safer forty-six planes failed to return during the year. Nine further aircraft brought back dead or wounded.

75 (NZ) Squadron Ground Crew

1945 started badly for the squadron when the new commanding officer, Wing Commander R.J. Newton DFC MiD RNZAF was lost with his crew attacking railway yards at Vohwinkel on the 1/2 January.

Because of allied air dominance daylight attacks were now taking place. This allowed for greater bombing accuracy, but it also allowed the German anti-aircraft gunners a better view! Three aircraft failed to return on the 21 March from an attack on Munster Viaduct. Operations were flown in support of the allied armies crossing of the river Rhine in mid-March.

The last casualty on the squadron was Sergeant R.S. Clark RAF who was killed by flak over Bremen on the 22 April.

75 flew its last operation on the 24 April to attack railway yards at Bad Oldesloe. All aircraft returning safely.

A large part of Holland was still in German hands. The civilian population was desperately short of food and in real danger of starving to death. A truce was arranged with the Germans to allow the RAF and the USAAF to drop food supplies. This was known as ‘Operation Manna.’ Supplies were dropped from the 29 April until 4 May.

The war in Europe ended on the 8 May.

Seven aircraft had failed to return from operations and a further seven returned with dead or wounded or crashed on return.

75 were now tasked with flying ex POW back to England. By the 24 May 2219 men had been repatriated.

In July, the Squadron moved to Spilsby in Lincolnshire and re-equipped with the Avro Lincoln bomber. The war in the Far East was still to be won and 75 were tasked to join what was known as ‘Tiger Force’ to bomb the Japanese home islands. Before they were ready to depart for the Far East atomic bombs were dropped on Japan and the war finally came to an end.

On the 15 October, the Squadron was disbanded.

In all 1139 members of 75 (New Zealand) Squadron lost their lives.

On the 1st of April 1946, the 75 number plate was transferred to the RNZAF in perpetuity in recognition of the squadrons’ wartime exploits.

AKE AKE KIA KAHA (For Ever and Ever Be Strong)

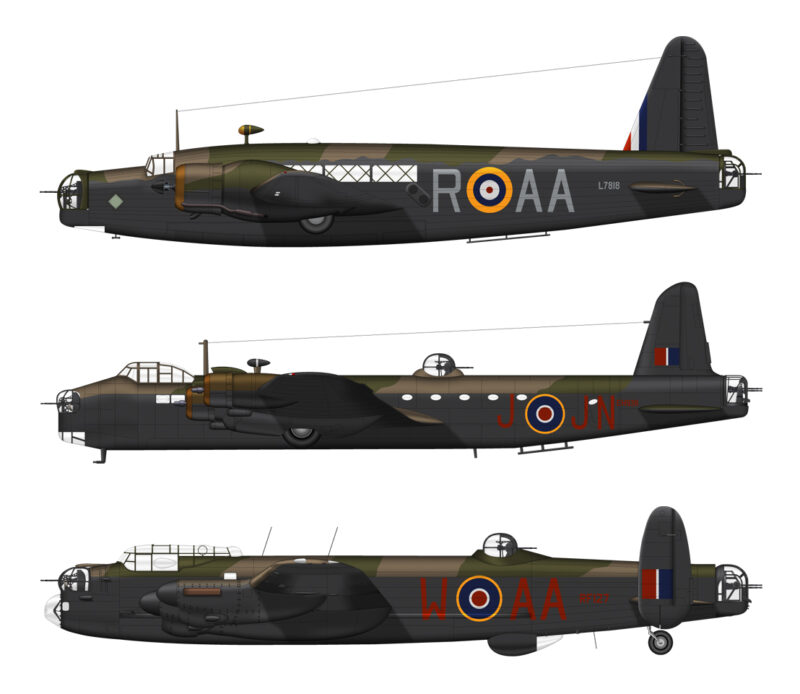

Aircraft of 75 Sq

August 4, 2024