Operations

Operations

After D-Day: Oil Targets

Although Allied senior air leaders had identified the German oil industry as a key target system for strategic bombing as early as 1940, under Harris, Bomber Command had focused more on German cities and industries, especially the centres of military production. This was to change after D-Day.

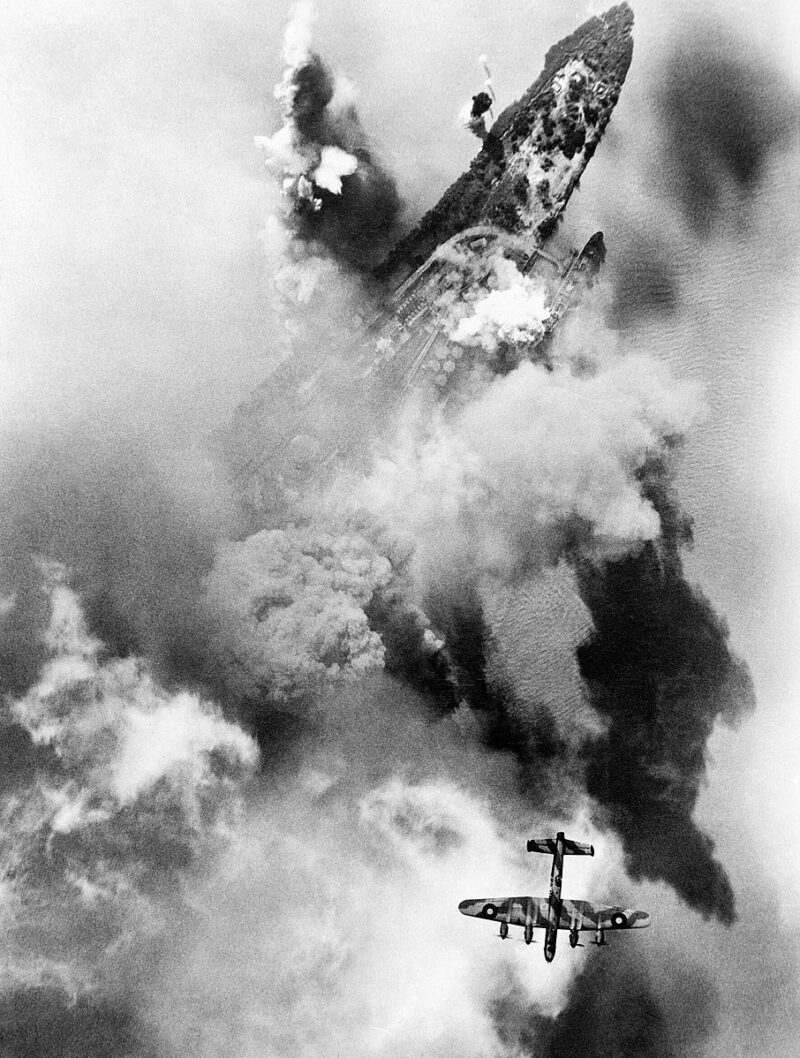

A Handley Page Halifax of RAF Bomber Command over the target during a daylight raid on the oil refinery at Wanne-Eickel in the Ruhr, 12 October 1944. (Credit: Imperial War Museum).

Germany was especially vulnerable to systematic attacks against its oil industry. Greater Germany (prewar Germany and Austria) had very few domestic oilfields, providing just ten percent of its petrol, oil and lubricant (POL) requirements. Germany imported oil from the Soviet Union (until the invasion of that country in June 1941) and from Hungary and Romania when these two countries became German allies.

Given the limited quantities of crude oil from German-controlled oilfields, the German war effort depended extremely heavily on production of POL from twenty-five production plants, which turned coal into oil. These plants were large, complex facilities not easily dispersed or moved underground.

Before D-Day, the Allies had conducted several attacks on German oilfields, oil refineries and synthetic oil production plants, but these attacks were episodic, for example, the American attack on the oilfields and refineries at Ploesti, Romania, in August 1943. With little or no follow-up, they only temporarily stopped the production of POL products at these facilities.

A USAAF B-24 Liberator, piloted by Robert Sternfels, as it emerges from a pall of smoke during the attack on the Astra Romana refinery on 1 August 1943. (Credit: National Museum of the UA Air Force)

Confirmation of the oil facilities’ importance and vulnerability were picked up by Bletchley Park’s Ultra intercepts and, together with other intelligence reports. resulted in in the oil targets becoming an increasingly important target in 1944.

Starting in May 1944, the attacks, especially on the synthetic oil production plants, became more systematic, and more successful. Allied planners began using aerial photographs to monitor the German reconstruction efforts and then would launch a new attack against a specific plant as it was nearing full production capability.

From September through to the end of the year. POL targets were now the highest priority. The around-the-clock bombing of the German oil industry reduced the production of petroleum, oil and lubricants by more than 90 percent, resulting in severe shortages of gasoline for German mechanized and motorized divisions and the Luftwaffe.

An Avro Lancaster of No. 514 Squadron RAF over the target during a Bomber Command attack on oil storage tanks at Bec d’Ambes in the Garonne estuary, 4 August 1944.

(Credit: Imperial War Museum).

Not only were the bombers successful; in so doing they improved the likelihood of safety for future operations. The growing shortages of POL products forced the Luftwaffe to shorten its pilot training program, resulting in growing numbers of relatively inexperienced pilots at the same time as Allied crews were growing in numbers and experience. Additionally, the Luftwaffe experienced increased losses of its experienced pilots as they had to enter aerial combat more frequently to “shepherd” the new pilots.

On the ground, increasing numbers of German Army mechanized and motorized units literally began running out of fuel on the battlefield. These desperate conditions, led to the December 1944 Ardennes offensive, aimed at capturing Allied fuel supplies at Antwerp. Not only did it ultimately fail, but it also used up much of Germany’s remaining fuel reserves.

The POL bombing campaign had the additional benefit of significantly decreasing the production of nitrogen, limiting the production of munitions for weapons.

By December 1944, Albert Speer, the German Minister for Armaments and War Production, viewed the systematic attacks on Germany’s oil industry and the resulting fuel shortages as “catastrophic.”

Sir Arthur Harris had been reluctant to systematically attack the oil industry but acknowledged post-war that the campaign was “a complete success” with the qualifier: “I still do not think that it was reasonable, at that time, to expect that the [oil] campaign would succeed; what the Allied strategists did was to bet on an outsider, and it happened to win the race.