Stories

Stories

Building Airfields

As well as training up aircrew and building aircraft, a massive network of airfields – for both frontline and training – would be needed for Bomber Command to operate. From just thirty-three permanent stations in 1939, by the end of the war Bomber Command squadrons had operated from 170 airfields across England and Scotland. Construction of airfields, hangers, operations and accommodation would be a major task.

Oblique aerial view of RAF Wellesbourne Mountford, Warwickshire, from north-north-west. Vickers Wellingtons of No. 22 Operational Training Unit can be seen occupying some of the circular dispersals off the perimeter track. The building of the technical site (middle) is almost complete, with the exception of one of four Type T2 hangars, which is still under construction. The domestic site, comprising huts and single-storey buildings, lies behind. The B4086 leading to the village of Wellesbourne Mountford (off left) runs by the airfield perimeter in the foreground.

(Credit: Imperial War Museum).

At the outbreak of war the RAF had a force that equalled less than half that of the Luftwaffe. Fighter Command had only 1,500 aircraft, many of which were already outdated. Bomber Command had 920 aircraft, but nothing was bigger than a twin-engined aircraft with limited capabilities.

While there was an intense focus on increasing the number and capability of aircraft, and training the crews to fly them, so there had to be enormous effort put into developing new airfields where these planes would be based. This was particularly so for Bomber Command as the, larger and heavier aircraft required a new standard for all future airfields to be built. And they had to be constructed at scale and at pace.

Standard Specification

Airfield specifications were laid down by the British Air Ministry Directorate-General of Works (AMDGW). The Class ‘A’ airfield became the standard airfield design for new bomber airfields.

These were formed around three intersecting runways, ideally at 60o to each other. Initially the Class ‘A” initially prescribed a main runway of 1,400 yards length (1280m) aligned, where possible, southwest to northeast. Later this was increased to 2,000 yards (1830m) to cope with larger bomb and fuel loads.

The subsidary runways were prescribed as 1,400 yards long (1280m). All three runways were to be 50 yards wide (46m). In addition, an extension of 75 yards (70m) was provided alongside the runaway to allow for emergency landings and another grass strip clear of all obstacles was to be provided, these measured 400 (366m) and 200 yards (183m) respectively.

The runways were connected by taxiways called a perimeter track (peri-track), of a standard width of 50 feet (15 m).

Hardstands were placed along the perimeter track, to allow aircraft to be dispersed some distance from each other so that an air attack on the airfield would be less likely to destroy all the aircraft at once. Dispersal also minimised the chance of collateral damage to other aircraft should an accident occur whilst bombing-up. Hardstands were either of the Frying-Pan or Spectacle Loop type, with the Spectacle type being the easiest in which to manoeuvre aircraft.

The hardstands were also made of concrete, with their centres at least 150 feet (46 m) from the edge of the track and the edges of each hardstand separated from each other by a minimum of 150 feet (46 m).

Other facilities needed for operations, technical services, maintenance sheds plus the living quarters – dining, accommodation and recreations were also typically dispersed around the airfied to further reduce the risk of damage if attacked.

RAF Bassingbourn in 1945, highlighting the Frying-Pan and Spectacle Loop aircraft disposals.

(Credit: United States Army Air Forces, piblic domain)

Constructing the Airfields

As Europe descended toward war, and following the signing of the Nazi-Soviet pact in August 1939, the British Government immediately passed the Emergency Powers (Defence) Act. Amongst far-reaching powers, the Act gave the Air Ministry the authority to requisition suitable land across the country for use by the RAF.

By the outbreak of war, 100 sites had been acquired, with the purchasing boards able to be ‘particular’ in their choice of location, something that was quickly disregarded as the war progressed. Once a suitable site had been identified and examined, the local geology had to be established where possible. This has not been necessary for grass runways, but to prevent heavier aircraft from bogging down, or the risk of flooding closing an airfield, well-drained soils were absolutely paramount.

When a suitable site had been identified, a construction tender was required. This created its own complications as the need for secrecy was of the utmost importance, and so little of the detail was released other than an approximate location.

As the war progressed, the number of construction companies involved became fewer and larger – many went on to be major construction companies post war. Nonethelss, no major airfield would generally be completed by one single contractor, as the whole process required a wide range of skills based operations

New airfields were highly labour intensive projects requiring an enormous workforce and extensive heavy machinery, little of which were available in the early 1940s. Irish labour provided the backbone of the initial workforce, whilst heavy plant came in from the United States. At its peak there were some 60,000 men employed on airfield construction, all of whom were unable to spend their time rebuilding the devastated towns and cities of the UK.

The material needs for building runways of an airfield suitable for heavy bombers were approximately 18,000 tons of dry cement and 90,000 tons of aggregate. Expected stress factors of 2,000 pounds per square inch led to runway thicknesses of six to nine inches of concrete slab laid on a hardcore base, covered with a layer of asphalt.

In areas where there was no natural rock, such as East Anglia, stone had to be imported for the hardcore. Up to six trains ran daily from London to East Anglia carrying rubble from buildings destroyed in Luftwaffe raids. This material was then used as hardcore for the airfields, to take thewar back to Germany.

To complete an A-Class airfied for heavy bombers would take a 1000-strong labour force about eighteen months. Such was the rate of construction that in 1942, the peak year of building, an average of one new airfield was coming into operation every three days. The runway construction time – from foundations down to receiving the first bomber – was around six months.

Of course an airfield was much more than runways and hardstands. Pre-fabricated structures were used for for a range of buildings including the T-Type Hangar and Nissen accommodation huts, medical facilities and other communal and administrative buildings.

Such was the pace of construction that it created issues for powerplant, workshop and other technical accommodation providesr to keep up with demand, at least until the end of 1943.

Standard lighting systems were required – the Mk II system being adopted which could be operated from the watch office and which was highly effective in reducing the time needed to land bombers at night.

As the war progressed, the Royal Air Force Airfield Construction Service began taking a greater role in airfield construction, diversifying away from their original role as repairers of damaged airfields sites and expanding capacity at existing pre-war sites.

In 1942, the United States joined the European theatre, sending their own Engineer Aviation Battalions to the U.K. Their task was to build their own airfields ready for the huge influx of men and machines that was about to arrive. The first site completed by the Americans and opened in 1943, was Great Saling (later renamed Andrews Field), built by the 819th engineer Aviation Battalion. Not being experienced in U.K. soils, it was a steep learning curve fraught with a number of initial problems.

The airfield construction programme was surely one of the greatest infrastructure efforts in history. Some 360,000 acres of airfields covered the UK. In Britain’s Military Airfields, author David J Smith states that the construction of runways and taxiways alone (and there was a lot of vehicular roads as well) amounted to the equivalent to a thirty-foot wide highway, 9,000 miles long running from London to Beijing. Construction had used thirty million tons of hardcore and eighteen million cubic feet of wood along with, with over 350 thousand miles of electrical cable. All for the RAF Bomber Command to fly.

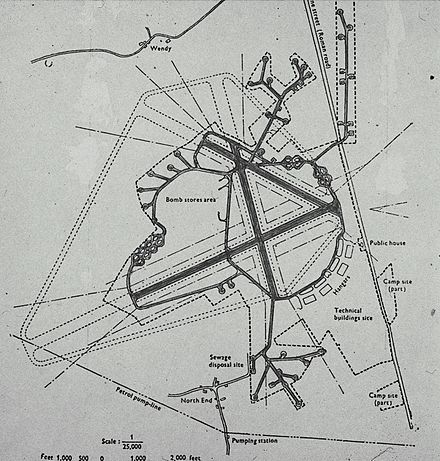

The layout at RAF Graveley, a class-A airfield constructed in WWII

(Credit: Imperial War Museum)