Operations

Operations

D-Day and the Battle of Normandy 1944

D-Day, the beginning of the liberation of Western Europe, was a turning point of WWII. Bomber Command efforts had been critical in the lead-up to Operation Overlord (the Battle of Normandy). Now an unprecedented joint campaign of both the RAF and US Air Force – fighters, bombers, transport and coastal operations – collectively provided the aerial fire power and protection for naval and land forces that contributed to the success of the landing and the subsequent defeat of Germany. NZBCA’s focus is, of course, on the role of Bomber Command throughout the war, but it would wrong to look at the bomber’s contribution to Overlord in isolation, without recognition of the combined strength of Allied air power – the largest and arguably most successful air force ever gathered.

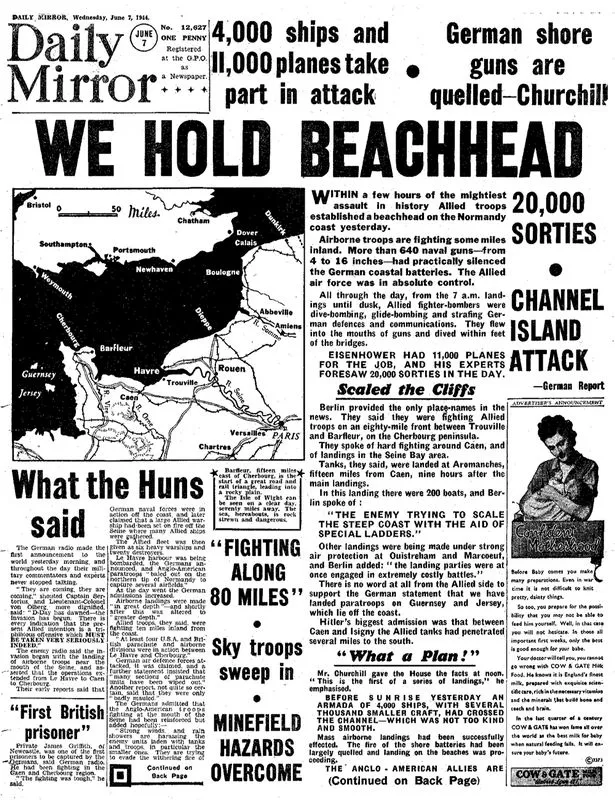

The front page of the Daily Mirror brings the news that the public have longed for – the Allies had landed in France.

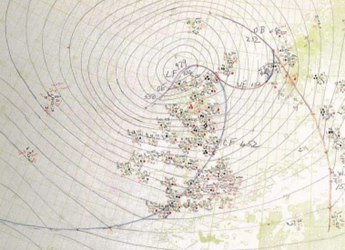

Meteorological flights

By the dawn of 6th June, the RAF had already influenced timing of the invasion. Originally scheduled for June 5, it had been postponed due to weather for 24-hours. Any further delay and the operation could not begin for another two weeks.

Meteorological flights far over the North Sea and the Atlantic were needed to make the critical decision to begin the attack. Specially equipped Halifax Bombers were operating out of Scotland, flying 10-hour weather gathering sorties.

They would go out flying at 1500ft. Every fifty nautical miles they would take a series of readings from the nose of the aircraft – the type and amount of cloud, the top & base of the cloud, visibility, wind speed, & temperature. Every two hundred miles, they would descend to sea level to read the sea level pressure.

Over the course of 4-5 June, information from these flights enabled the met team led by Group Captain James Stagg, to predict a temporary break in the weather, sufficient for General Dwight Eisenhower, Supreme Allied Commander, to order the invasion to proceed without further delay.

A forecaster’s chart for 1800 GMT on Sunday 4 June 1944. It was plotted in the hour before Group Captain Stagg briefed Eisenhower that an interlude in the weather was expected on Tuesday 6 June.

On D-Day, 6 June 1944, the greatest invasion fleet ever seen crossed the English Channel. The invasion force included 7,000 ships and landing craft manned by over 195,000 naval personnel from eight allied countries.

Bomber Command

On the night of 5/6 June, Bomber Command had sent over more than a thousand heavy bombers to pound beach defences in Normandy. Other bombers flew on diversionary operations, parts of an elaborate deception scheme to confuse the Germans.

In an incredible display of flying skills, Nos 218 and 617 Squadrons slowly flew back and forth low over the Channel, dropping strips of metal called ‘window’ intended to show up on German radar screens as masses of ships. Effectively it appeared that two more Allied invasion fleets were creeping across the English Channel, diverting German troops and resources to Boulogne and Le Harve and away from the Normandy beaches.

The RAF flew Boeing Fortress’ equipped with powerful electronic devices such as the ‘Airborne Cigar.’ Their task was to jam German radio frequencies, adding to defensive confusion.

Transport Command

RAF Transport Command had also been very busy. The first Allied troops to land on D-Day were an airborne assault team to seize Bénouville Bridge. These men were successfully delivered to their objective in gliders, towed across the Channel by RAF tug aircraft (see page 28).

Soon after, more squadrons of transport and glider tug aircraft, such as Halifax and Douglas Dakotas, flew most of the British 6th Airborne Division into Normandy, a few hours before the first troops hit the beaches. Their role was to seize control of other vital bridges and roads in and out of the invasion area, stopping German reinforcements from reaching the beaches.

Dummy parachutists, nicknamed Ruperts, were dropped from the air. Made of sackcloth and filled with sand and straw in the crude shape of a dummy parachutist, many were designed to produce gunfire sounds or fire flares. Some 450 Ruperts were dropped on the night of the invasion to add to the confusion for the German defenders.

Coastal Command

Perhaps the unsung heroes of D-Day were the squadrons of RAF Coastal Command. The Germans had planned to resist any invasion with extensive submarine numbers attacking the expected naval armada from both north and the south. Intensive Coastal Command patrols protected both approaches.

Using radar to identify enemy submarines on the surface, these flights would cover every part of the critical area, from southern Ireland to the mouth of the Loire, 20,000 square miles, every 30 minutes, day and night for an indefinite period.

Thirty minutes was chosen because U-boats were believed to use, in a crash dive, the same amount of electrical energy as could be charged into the batteries in 30 minutes on the surface. If the U-boats were forced to crash dive every 30 minutes, they would gain nothing from charging their batteries while on the surface and they would arrive in the fighting-zone with their crews exhausted, with flat batteries and little compressed air required to surface.

Within four days of the landings, of the 49 U-Boats launched in the south, six had been sunk and another six seriously damaged. Just one had managed to attack the invasion fleet. By the end of June, fourteen U-Boats had been sunk and fifteen seriously damaged. Not a single invasion ship had been lost to submarines.

A Coastal Command Beaufighter carrying the invasion stripes used to identify Allied aircraft D-Day and throughout the Battle of Normandy.

Fighter Command

Closer to the actual landings, fighters protected the fleet and the beaches. Cover was so heavy that only two enemy aircraft managed to attack the beaches on the first day of the landings.

As the days passed, the pressure was kept up. Transport Command brought in more troops and dropped much needed supplies, while also flying wounded soldiers back to hospitals in England.

Bombers continued to real havoc on transport links and German reinforcements, destroying counterattacks before they could start. Fighters gave close support to the troops on the ground with rockets and bombs, attacking tanks and strong points and giving air cover to the vulnerable fleet and beachhead.

2nd Tactical Air Force

As the beachhead slowly expanded parts of the 2nd Tactical Air Force (2TAF) began to deploy to advanced landing grounds. By 9 June, RAF fighters were flying from bases in France for the first time since 1940.

Air Observation Post aircraft could direct Allied artillery fire with such devastating accuracy that their mere presence over the battlefield was enough to make some German troops and artillery cease fire in case they drew attention to, and fire, on to themselves.

From the middle of June 2TAF took an increasing role in attacking German positions and armoured vehicles. This created one of the enduing images of the campaign – RAF Hawker Typhoons destroying German tanks en masse with rockets. In fact, the rockets were quite an inaccurate weapon, but they were still highly effective when used in numbers.

The Commanding Officer of No. 486 (NZ) Squadron, Squadron Leader J H Iremonger, standing by the cockpit of Hawker Tempest Mark V, ‘SA-F’.

(Credit: Imperial War Museum)

One example of tactical airpower’s effectiveness was Panzer- Lehr Division’s eighty-mile dash to the coast. Ordered to move towards Bayeux on the morning of 7 June, the columns were discovered almost as soon as they took to the road.

The commanding officer of this elite unit described the trek as ‘‘a fighter-bomber racecourse,’’ and though the division lost only five tanks, it wrote off or abandoned eighty-four other armoured vehicles and 130 trucks and other support vehicles, serious losses for a division not yet in action.

While 2TAF engaged in a war of attrition with the German Army, Bomber Command was called back repeatedly to try and blast holes in the German defences and allow a breakout from the beachheads. In these hectic times Bomber Command averaged 5,000 sorties a week – more than for all the first nine months of the war.

From late July the Germans launched their new offensive on Britain, using V-1 flying bombs. Increasingly the task of finding and bombing their launch sites, Operation Crossbow, drew RAF resources from the Normandy campaign.

Falaise Gap.

Through the middle of August, as attrition – largely from the air – wore down the German defences, both the British and American forces in Normandy began to break out from the beachheads. As they did so, the German Seventh Army was increasing surrounded in a pocket, until they were almost cut off. The only escape route was through what became known as the Falaise Gap.

2TAF relentlessly attacked both the pocket and the gap, until the gap was finally closed in late August. Over 60,000 Germans were killed or captured in the Falaise pocket, and 95% of their armour destroyed. The German Army in France would never recover from this blow.

Conclusion

The RAF, in tandem with the US Air Force, had played a critical role in the Battle for Normandy. They had flown 225,000 sorties, at the cost of over 2,000 aircraft and 8,000 crewmen. They had swept the skies clear and hammered the enemy on the ground, opening the way for the Allies to land.

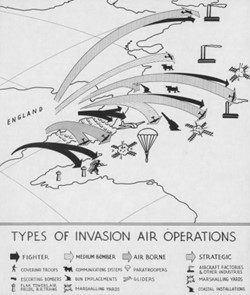

A graphic depiction of the various forms of airborne missions flown on D-Day.

Allied air power had devastated German transport and communication, hindered reinforcements and allowed the beachhead to be established and grow. Finally, they had cleared the way for the Allies to break out and begin the advance that would free Europe.

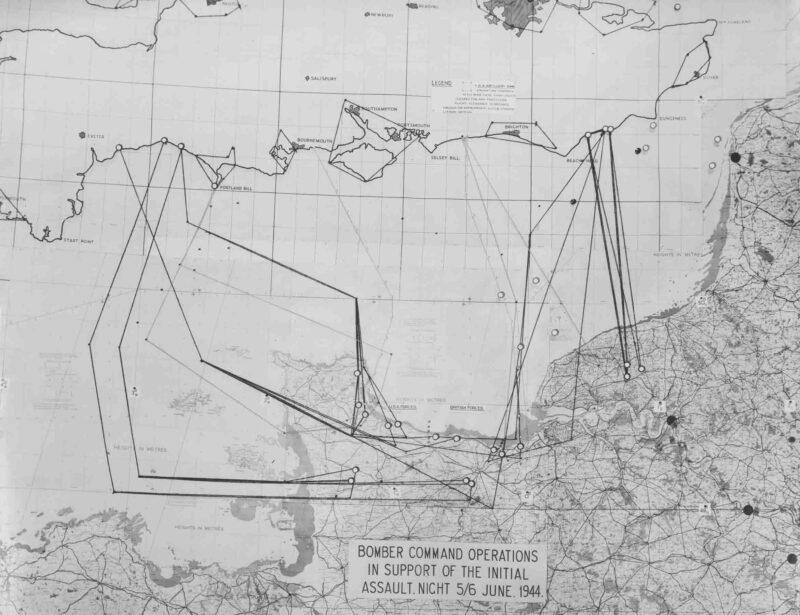

A map of Bomber Command operations on the night of 5/6 June in support of the initial assault.

Note the map does not depict RAF bases but rather the points at which, having formed up, departed the English coast.

(Credit: Royal Air Force Museum).