Operations

Operations

The Battle of the Ruhr 1943

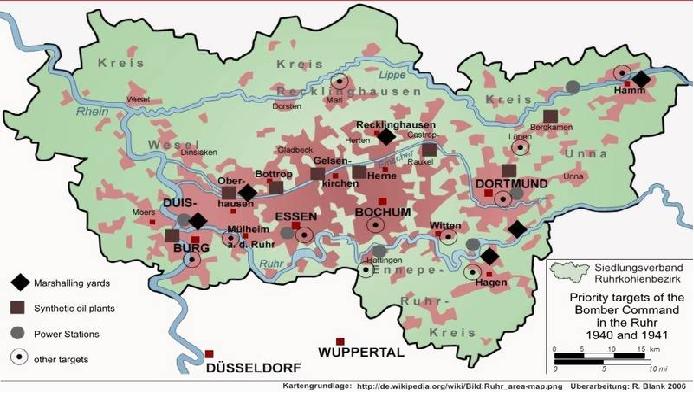

Illustration from the book ‘The Ruhr 1943’ by Richard Worrell

(Credit: Graham Turner / Osprey)

The Battle of the Ruhr 1943

Operation Chastise, the famous Dambusters raid is an extraordinary example of skill and technology. But in terms of strategic intent, it was just one operation, albeit a mighty one, in the context of the much larger Battle of the Ruhr. As the first of three major bombing offensives launched by Bomber Command in 1943, this battle is considered the turning point in bomber operations in the war, aggressively taking the attack to Germany.

The four months from March 1943 saw one of the most dramatic battles of the air war – a battle in which a veritable fortress was assaulted from the air in a series of short but intense actions of almost incredible ferocity. More than 18,000 sorties were flown. Almost nine hundred aircraft were lost and another two thousand damaged. And a staggering six thousand aircrew killed, among them many New Zealanders. This is the Battle of the Ruhr.

In 1943, Arthur Harris, as Air Officer Commanding-in-Chief Bomber Command, now had at his disposal the men and weaponry capable of taking the fight to Germany.

Almost four hundred operational heavy bombers were now available, supported by 180 mediums, crewed by the influx of airmen from around the Commonwealth.

They were now directed by the Pathfinders who could more accurately mark targets for the bomber stream and the bombers themselves were equipped with Oboe for navigational guidance and H2S radar.

The first campaign was to have Its targets, Germany’s industrial heartland, the cities and towns of the Ruhr Valley – Essen, Gelsenkirchen, Duisburg, Mulheim and Oberhausen and the nearby cities of Dusseldorf and Cologne which were part of the same industrial complex.

Soon to be known as “Happy Valley” by bomber crews, the Ruhr would prove a difficult target to attack due to the haze generated by its industrial plants and the high concentration of German defences, flak, searchlights, and the Increasing numbers of German night fighters, equipped with radar and various electronic targeting devices.

The Ruhr was strategically important for the war to be won. Within its boundaries lay a great many of the factories that forged the guns, tanks, and engines of war upon which the enemy forces depended.

Moreover, as the largest centre of heavy industry and coalmining in Europe, the Ruhr not only provided finished products of all kinds but almost the whole of the coal and steel needed by other industries in Germany to produce war materials.

The flagship was the Krupp works in Essen, the principal manufacturer of large calibre artillery, tanks, armour plate, and other high-quality armament, and the second largest producer of iron and coal in Germany. Steel from the Ruhr was used to produce U-Boats, aircraft, and missiles.

Some of its coal deposits were being utilised for synthetic gasoline manufacture and other commercial chemical processes.

The offensive opened on 5 March 1943 when 442 aircraft raided Essen, a major industrial centre that was vital to the German war machine.

After making landfall at Egmond on the Dutch coast, the bombers flew directly to a point fifteen miles north of Essen, where Pathfinders had yellow-marked the route indicators on the ground as a guide.

From there the crews began a run-up to the target at a rate of eleven a minute – the attack planned to last thirty-eight minutes.

Flying in ahead, Oboe equipped Mosquitos dropped red target indicators, with Lancaster Pathfinders dropping green indicators, aimed at the reds, as back-up throughout the attack.

The markers enabled the attack to be concentrated and soon there an almost solid ring of fire, two miles in diameter. At least half of the bomb load had fallen in the centre of the city, a particularly good result and just fourteen aircraft were missing. The rate of loss would grow markedly as defences responded to the concentrated attack on such a narrow target.

Five more attacks were launched against Essen alone over the next three months and by the end of July, both the huge Krupps works covering several hundred acres in the centre of Essen, and the town itself had suffered greatly. On this one town, 3260 sorties were flown with the loss of 138 aircraft and their crews.

But Essen was only one of many targets. In the weeks to come, Ruhr targets were raided forty-three times on 39 nights. Bomber Command dispatched a total of 18,506 sorties. 58,000 tonnes of bombs rained down on the valley – more than the Luftwaffe dropped on Britain in two years (1940-41).

While casualties on that first raid were relatively light, these mounted quickly as defences grew steadily in strength, tactics, and skill, responding to the attacks night after night. 872 aircraft failed to return (4.7%) and a further 2,126 were damaged, with some 6,000 aircrew casualties. On some nights as many as thirty percent of aircraft came back damaged or were lost.

The crews, largely isolated at their bases, knew little of Harris’ overall plan other than from bulletins from Group or High Wycombe. What they knew was that they were flying night after night to some of the most heavily defended targets in Germany and suffering significant losses.

The concerted attacks against the Ruhr continued until July 1943, when the longer nights of summer reduced the effective window for night-bombing. The climax came on 25 July when more than seven hundred bombers made their last attack of the battle against Essen.

For the loss of twenty-three aircraft, it is estimated that the attack, concentrated within a narrow strip about 2km wide, did more damage than all the previous Essen raids combined.

Historians dispute the impact of the Battle of the Ruhr. Some argue that while, by late July, Harris thought that the Ruhr has been reduced to chaos and that German arms production had been substantially cut, that in fact the Germans had already begun to disperse industry.

In part this is true, nonetheless, the status of the Ruhr was changed forever from that of the home front to a war zone with an emergency staff placed to control over the regional economy. Workers had to be accommodated in camps, ready to be sent to factories that were still open, but these were expedients.

Significantly, the German night defences could not stop the RAF bombers from inflicting great disruption on the war economy. Steel production was cut at a time that Albert Speer, head of the Reich Ministry of Armaments and War Production, was expecting a massive increase in output in response to the war in the East.

Because of the damage, Germany was unable to increase the monthly aircraft production for the Luftwaffe – hampering their air defence against future bombing attacks.

And in the rest of the armaments economy there was no increase in production until 1944. Having reorganised the steel allocation system, the German planners were forced into a large cut in the ammunition production programme to compensate.

All over Germany, the destruction in the Ruhr caused shortages of parts, castings and forgings, and a sub-components crisis, which reached far beyond heavy industry.

In effect, Bomber Command had stopped Speer’s armaments miracle in its tracks. Notwithstanding the loss of so many bombers and most of their crews, we can only imagine how many more lives may have been saved because of their sacrifice, weakening the German military apparatus.

Perhaps the political impact is best summed up by Nazi Propaganda Minister, Joseph Goebbels, who wrote in his diary on 10 April, after visiting Essen to see for himself,

“…the damage…is colossal and, indeed, ghastly….The city’s building experts estimate that it will take twelve years to repair the damage.”

Goebbels blamed Reichsmarschall Göring and the chief of procurement, Ernst Udet, for negligence on a grand scale. On 8 May, Hitler told Generalluftzeugmeister Ernhard Milch, in charge of all Luftwaffe aircraft production, armament and supply, that either Luftwaffe tactics or technology was lacking and after meeting Hitler on the same day, Goebbels wrote,

“The technical failure of the Luftwaffe results mainly from useless aircraft designs. It is here that Udet bears the fullest measure of blame.”

Despite the overall losses, the scale of aircraft production in Britain and aircrew training across the Commonwealth meant that Harris’ daily availability of bombers had actually increased from 593 in February to 787 in August.

Having proven the impact of sustained attack on a target area, Harris would now turn his attention to Hamburg.

New Zealanders Flying to ‘Happy Valley’

New Zealanders were at the forefront of the attack on the Ruhr. 75 (NZ) Sq. was recently re-equipped with Stirlings, while other aircrew were dispersed across RAF squadrons. 75 (NZ) was represented in all the principal raids, including Essen, Duisburg, Dortmund, and Dusseldorf.

In New Zealanders with the Royal Air Force (Vol II), this battle is described as colossal battering match between air and ground. As the first aircraft approached, hundreds of searchlights would come on and the sky would quickly fill with bursting shells, the bombers flying through a barrage of fire and steel.

One pilot, describing the scene during the second Essen raid at debrief, described, “the searchlights, in huge cones, made a wall of light across the Valley.” Waiting outside the light would be the Luftwaffe night-fighters, picking off unwary crew and damaged aircraft. Many bombers returned with parts of their wings or fuselage torn to shreds, literally flying back on ‘a wing and a prayer.

The experience of Flt.Sgt. Cole (50 Sq.) of Carterton captures the times. His aircraft was coned by searchlight after releasing their bombs. They evaded the lights, but a few minutes later they were caught again by blinding light and hit by flak and the rear gunner killed.

The aircraft flipped on its back, petrol pouring from one of its tanks. Somehow Cole regained control but then lost an engine to fire. The bomber was so unstable that he ordered the crew to prepare to bale out as he struggled with the damaged controls.

Eventually, by lashing back the rudder pedal with a leather strap, and then careful piloting he managed to get the Lancaster back to England and completed a forced landing.

The raid on Wuppertal (29-30 May) was an awful night for the RNZAF, among the single worst nights in the war over Europe. Twenty-one New Zealanders dead on eleven aircraft. Alistair Boulton, a navigator with 218 Sq. recalled the briefing by the Intelligence Officer, tapping the map for that raid, in Max Lambert’s ‘Night After Night’.

“Tonight, we’re going to Wuppertal…..a lot of people who work in the Krupps steel plants live there. We’re going to get them. They are in the war just as much as you and I. They’re making the shells and bullets that are going to get you, so you’ve got to get them.” What he said shocked some of the fellas, but it didn’t worry me. That is war.

Boulton’s Stirling survived that raid, just his second op. They were not so lucky four weeks later, brought down over the Dutch-German border.

Typical of many eventful flights was that of Sq. Leader Keith Thiele (DSO and DFC and Two Bars) of Christchurch and his 467 Sq. crew attacking Duisburg in early May. Nearing the city their Lancaster was severely damaged by a shell bursting under the fuselage. Continuing on, during final approach the aircraft was caught in a cone of searchlights and shells began to burst all around.

Just as the Bomb-aimer released their load, they were hit again, destroying the starboard outer engine. Almost immediately after the starboard inner was hit and the side of the aircraft ripped open along the pilot and bomb-aimers compartments.

Although dazed by shell splinters, Thiele managed to keep control and complete the long return trio home. Crossing the British coast, they could not retain height and Thiele made a crash-landing without injury to the crew. It was the second time the Thiele crew had returned on two engines.

As well as ground defences, the threat of night-fighters was very real. Sq. Ldr. J R St John (DSO and DFC and Bar) of Nelson (101 Sq.) was caught on outward flight by searchlights and first attacked by a Junkers Ju 88 which inflicted sever damage. Then, after diving to 3000 ft, they were attacked by a Dornier Do 217.

The Lancaster scored hits on the Dornier, but the Junkers returned setting fire to the starboard outer engine.

With the bomber losing further height, the crew jettisoned the bomb load to make their escape and set course for base – with one rudder, both turrets unserviceable and the fuselage and both petrol tanks badly holed. As well, one elevator was partly shot away and the controls almost severed. Somehow, despite this St John (says the official report) “with great skill and ability brought the aircraft back and landed it safely.

The New Zealand Squadron, 75 (NZ), now had a third flight of eight aircraft now operational and was able to increase its contribution to Harris’ offensive. By the close of the Battle of the Ruhr, they had despatched 225 aircraft across eighteen raids, dropping 566 tons of bombs. This despite the move to RAF Mepal at the end of June.

The Squadron lost seventeen Stirlings from these missions. The raid on Wuppertal noted earlier was particularly unfortunate, with four aircraft and crew lost. And a raid on Mulheim saw a further four aircraft lost. Among the crews killed on these two raids were twenty-eight New Zealanders.

While the main part of No.75 Squadron’s efforts was focused on the Ruhr, they like other also operated on other missions in the same months, deep into enemy territory to divert air defences and maintain pressure on other targets. Berlin, Munich, Frankfurt, Nuremberg, and Stuttgart were all attacked, stretching the night-fighter defences.

Typical 88mm air defence flak gun in position

Part of the huge Hindenburg Hall locomotive shop of the Krupps AG works at Essen, Germany, seriously damaged by Bomber Command in 1943 and further wrecked in the daylight raid of 11 March 1945.

Locomotive production did not resume after the 1943 raids, despite the fact this having equal priority with aircraft, tanks, and submarines, such was the dependence on rail transport for men, equipment, and other supplies. This severely disrupted transport of military equipment later in the war.

Other major war requirements whose production was seriously reduced because of the Essen attacks at this time included shells, fuses, guns, and areo-engine parts.

(Credit: F/O R R Broom, Royal Air Force official photographer)